An analysis by CViSB scientists at Scripps Research of billions of distinct antibody-producing immune cells sampled from human volunteers indicates that the human antibody “repertoire” is far larger than was once thought.

The finding, reported online on January 21 in Nature, suggests that humans may be capable of producing as many as 10^18, or one quintillion, distinct antibodies. The study also provides the largest single collection of antibody gene sequences to date, and points to the future medical use of antibody sequence information from individuals and large populations.

“Antibody repertoire information could soon be used to diagnose autoimmune diseases and chronic infections, for example, or to design vaccines,” says study lead author Bryan Briney, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Immunology and Microbiology at Scripps Research and PI of the CViSB Technology Core.

The study’s senior author was Dennis Burton, PhD, co-chair of Scripps Research’s Department of Immunology and Microbiology, who is also part of CViSB.

Antibodies are Y-shaped proteins that can grip bacteria, viruses and other biological targets very specifically and with high affinity as part of an immune response. They are produced by immune cells called B cells, which reside in the blood, spleen, lymph nodes and other tissues. B cells can be grouped into distinct clones, each of which produces antibodies with a unique set of target-gripping structures.

In principle, having the details of the antibody repertoire in individuals and in different populations would enable important scientific insights, as well as a wide range of medical applications. In practice, though, the amount of data involved has been considered prohibitively large. The billions of distinct arrangements of antibody genes in the B cells of an individual contain vastly more information than is in that person’s entire genome.

Due to the difficulty of gathering and analyzing such enormous amounts of data, scientists until now have been able to make only rough, theoretical estimates of the total human antibody repertoire. “A trillion possible antibodies are a commonly cited figure,” Briney says.

The good news is that recent technological developments have sped up sequencing methods, making projects on this scale less daunting. “We in our lab have also been able to develop software tools for processing billions of antibody sequences into a dataset that we can use,” Briney says.

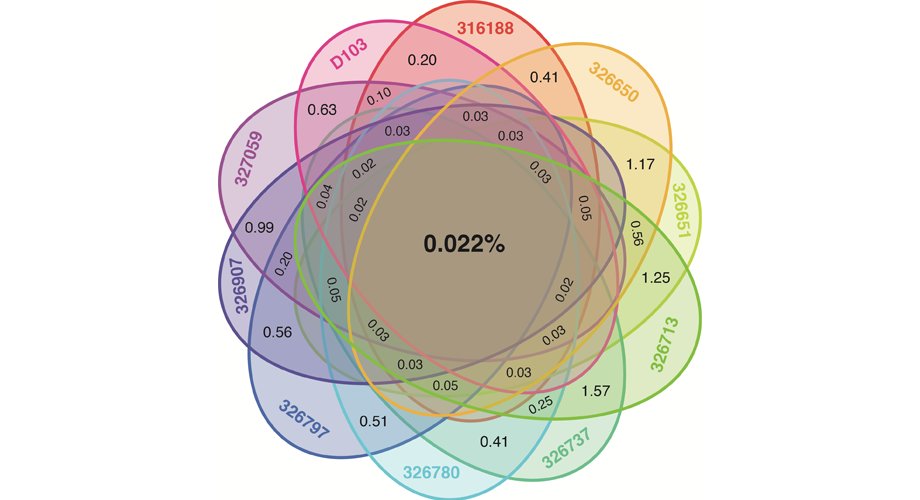

In the new study, he and his colleagues took blood samples from a group of 10 Californians between the ages of 18 and 30 that included men and women, Caucasians and African Americans. The researchers isolated the subjects’ B cells and sequenced the cells’ antibody genes. Focusing on the genes encoding the most variable, “heavy chain” segments of the antibodies’ target-gripping structures, the scientists assembled almost 3 billion distinct sequences.

Their analysis of these sequences showed that each subject’s antibody repertoire differed greatly, presumably due in part to their personal histories of infections and other immunological events. The analysis also suggested that, based on the repertoire diversity seen among these 10 people, the total human antibody repertoire could easily comprise as many as one quintillion – a million trillion – unique antibodies.

At the same time, the analysis showed there are some types of antibodies that most people tend to have. “This is very exciting—knowing these common features of the antibody repertoire should be very useful, for example, in designing vaccines,” Briney says.

He and his team plan to follow up with further antibody-sequencing studies in larger groups of people from around the world. They also plan studies of antibody repertoires as potential tools for diagnosing diseases, revealing infection histories, and potentially informing other clinical applications.

“Getting clinically relevant insights from this kind of information would be a big step forward, and we’re hoping soon to do that,” Briney says.

The authors of the study, “Commonality despite exceptional diversity in the baseline human antibody repertoire” were Bryan Briney, Anne Inderbitzin, Collin Joyce, and Dennis R. Burton, all of Scripps Research.

The research was made possible by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UM1AI100663, U19AI135995), the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) through the Neutralizing Antibody Consortium (SFP1849), and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard.