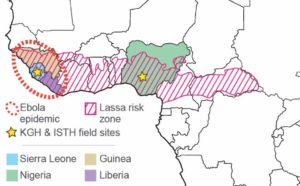

Figure 1. Ebola and Lassa in West Africa

The Ebola epidemic that ravaged West Africa from 2013 to 2016 is by far the largest outbreak ever recorded. Weak healthcare infrastructure, community resistance, and a slow uncoordinated international response, allowed the epidemic to spin out of control. The region, however, is no stranger to dealing with viral hemorrhagic fevers and ultimately managed to get the Ebola epidemic under control largely thanks to local community efforts. Lassa fever is caused by infection with Lassa virus and is hyper-endemic in West Africa (Figure 1).

Lassa fever is similar to Ebola in that infection with Lassa virus can lead to a severe hemorrhagic fever. Infections with both Lassa virus and Ebola virus can lead to deaths in more than 70% of hospitalized patients. It is estimated that tens of thousands of people die from Lassa fever each year. These numbers are likely underestimates, as the healthcare infrastructure in the affected countries is extremely weak, surveillance almost non-existent, and most patients never present in the hospital.

Despite the high case fatality rates of hospitalized Ebola and Lassa fever patients, some people appear to be able to quickly fight the viruses, whereas others die quickly from infection. Yet, what distinguishes fatal from non-fatal disease and the development of symptomatic versus asymptomatic infection, remain largely unknown and severely understudied. The goal of the Center for Viral Systems Biology is to uncover the virus and human factors that determine how infected individuals are able to better fight the viruses. We will achieve this goal by investigating the following three broad aims:

Aim 1. Define virus and host factors responsible for survival and non-survival in Ebola and Lassa fever patients.

Aim 2. Identify factors that play roles in the development of severe long-term symptoms in survivors.

Aim 3. Define factors that determine whether human individuals develop symptomatic or asymptomatic disease.

Working closely with local partners at Kenema Government Hospital and the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation, we will accomplish these aims by applying several ‘omics’ technologies, physiological measurements, and high-throughput experimental approaches to unique patient and survivor cohorts of Lassa fever and Ebola. We will develop novel predictive statistical models for identifying critical disease correlates and analyze large-scale data sets to pinpoint causal host-pathogen interactions.

By characterizing the molecular, physiological, and immunological networks that play critical roles in patient outcomes, it is our hope that our research will allow us to identify new targets for medicines and vaccines and inform personalized treatment strategies. These studies will also provide novel research frameworks and computational algorithms applicable to a wide range of other human pathogens.

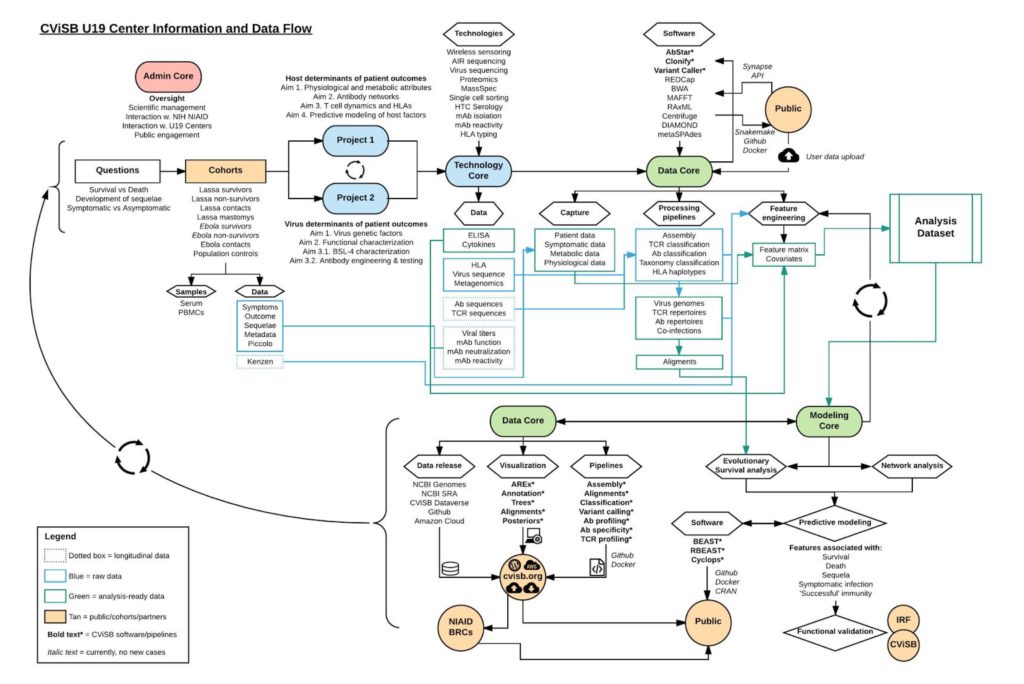

Finally, we are strong believes in the openness of science and the critical need for faster and more efficient sharing of scientific data and findings. To this end, all data and software tools produced as part of CViSB (Figure 2), will be released openly and without restrictions to the public as quickly as possible. We are hopeful that this will enable us to engage the larger infectious disease research community and provide tools and datasets that are helpful to a broad array of researchers.

Figure 2. Flow of information through the CViSB Center.